What is a Sculpture Court?

By Jill Vuchetich

Located in Gallery D/Perlman at the Walker Art Center is a small exhibition of sculpture from the Walker’s permanent collection. It’s a quiet space in which to contemplate the works on display. You can even take time to sketch the sculpture. Sculpture Court is both the name of the exhibition and an architectural description of the space.

A sculpture court is a deceptively simple concept, but many interpretations and decisions go into its creation. For example, it can be an interior or exterior space. It is generally a small, contained area, but it can also act as a connecting space or corridor. In describing a court, one must consider not only its size and shape, but also the lighting and, of course, the sculpture it holds. Each component adds complexity to a sculpture court that the viewer may overlook. Adding to the confusion, it can be called a court, plaza, or garden.

To begin to understand a sculpture court in a contemporary art museum, we need to go back to the Renaissance. The inspiration for European museum sculpture courts comes from the Italian Renaissance, when an interest in classical Greek and Roman culture was revived. Patrons of the arts, such as the Medici family in Florence, collected ancient sculptures for the Palazzo di Medici, commissioned by Cosimo the Elder; it contains an early example of statuary display. Artists, including Michelangelo and Donatello, visited frequently, drawing the figures from Greek and Roman mythology and later contributing sculpture themselves, such as Donatello’s Judith. Other members of the Medici family were enthusiastic collectors and builders, including Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, also in Florence, and Catherine de Medici, Queen of France.

Typically, a sculpture court includes freestanding artworks; however, many works collected during the Renaissance started as architectural elements, such as the caryatids supporting the Erechtheion at the Acropolis. Placement of the sculptures in a dedicated space, where they were admired and studied on their own, was a new concept.

Centuries later, the United States experienced a boom in art-collecting and museum-building, referred to as the American Renaissance; it was also inspired by the Greek and Roman classical period, as well as by the Italian and French Renaissance. During this period of the 1800s, the architects McKim, Mead, and White designed many public buildings: these included the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1897, the wings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1912, and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Mia) in 1915. In the plans for Mia, a sculpture hall is to the left of the main entrance, which resembles a Greek temple.

Beginning in the 1930s, architectural taste steered away from the classical model toward modern and contemporary styles. Designed by architects Philip Goodwin and Edward Durrell Stone, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) became the model for contemporary architecture when it opened in 1939. The new model abandoned small, enclosed galleries of the classical style in favor of open, lofty spaces, allowing for multiple ways of configuring or temporarily partitioning spaces for exhibition purposes. MoMA’s director Alfred Barr and architecture curator, John McAndrew, established the sculpture garden in an enclosed exterior court, 100 feet by 400 feet, at the back of the museum. Though an afterthought, it proved to be popular; over the years, the original garden was renovated and expanded by other well-known architects, notably Philip Johnson, MoMA’s curator of architecture in the 1950s.

As museum buildings proliferated in the 20th century, architects would design them to include courts or gardens. They could be in a classical style like at Mia, or modern as at MoMA. They could be interior or exterior, small or large spaces. Many serve an architectural purpose of connecting one side of a museum to another. And because museums are ever-changing environments, they could simultaneously incorporate both classical and contemporary, as well as other influences.

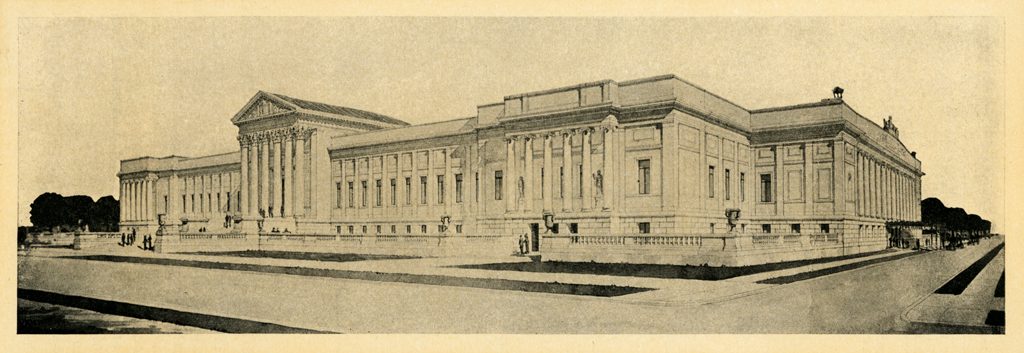

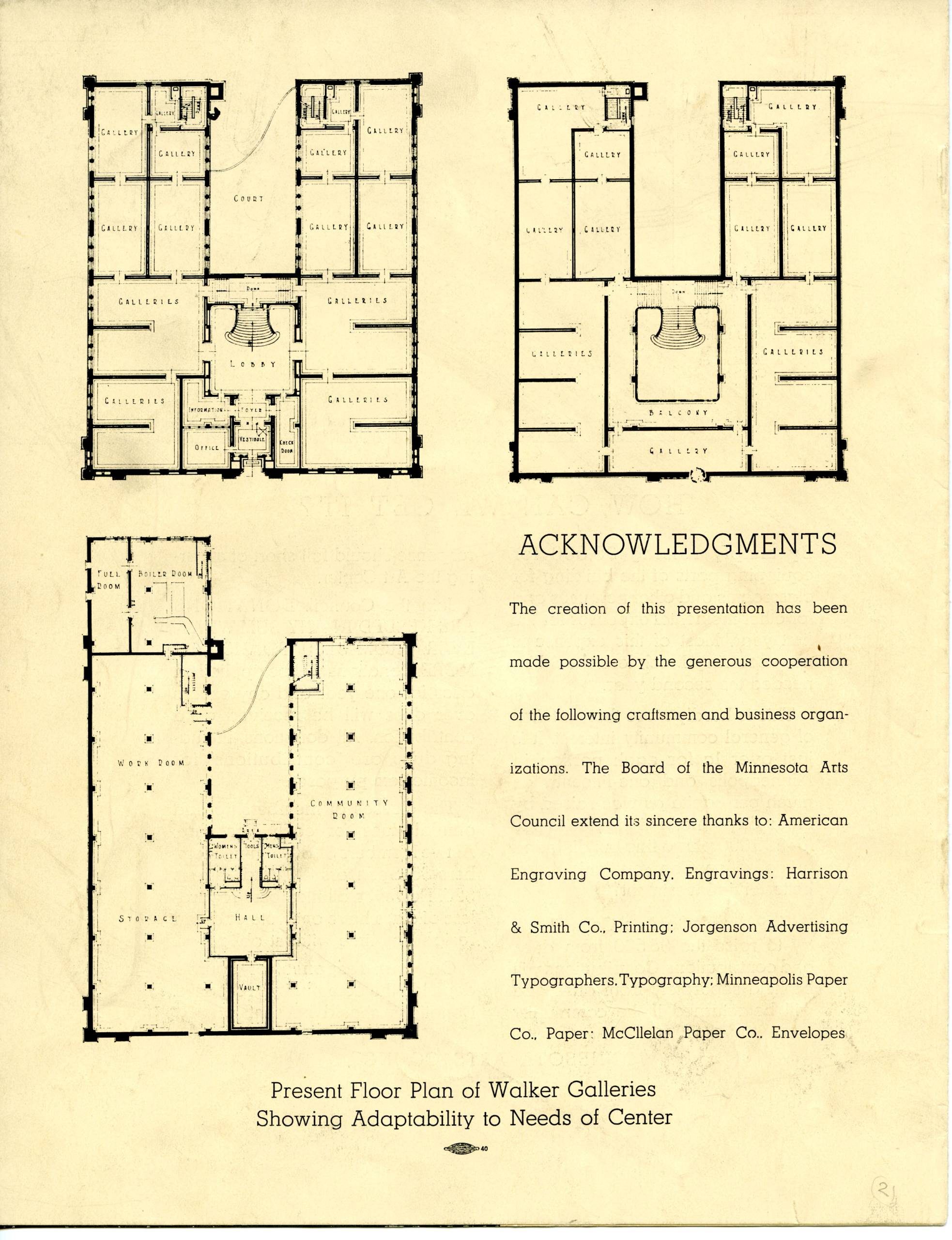

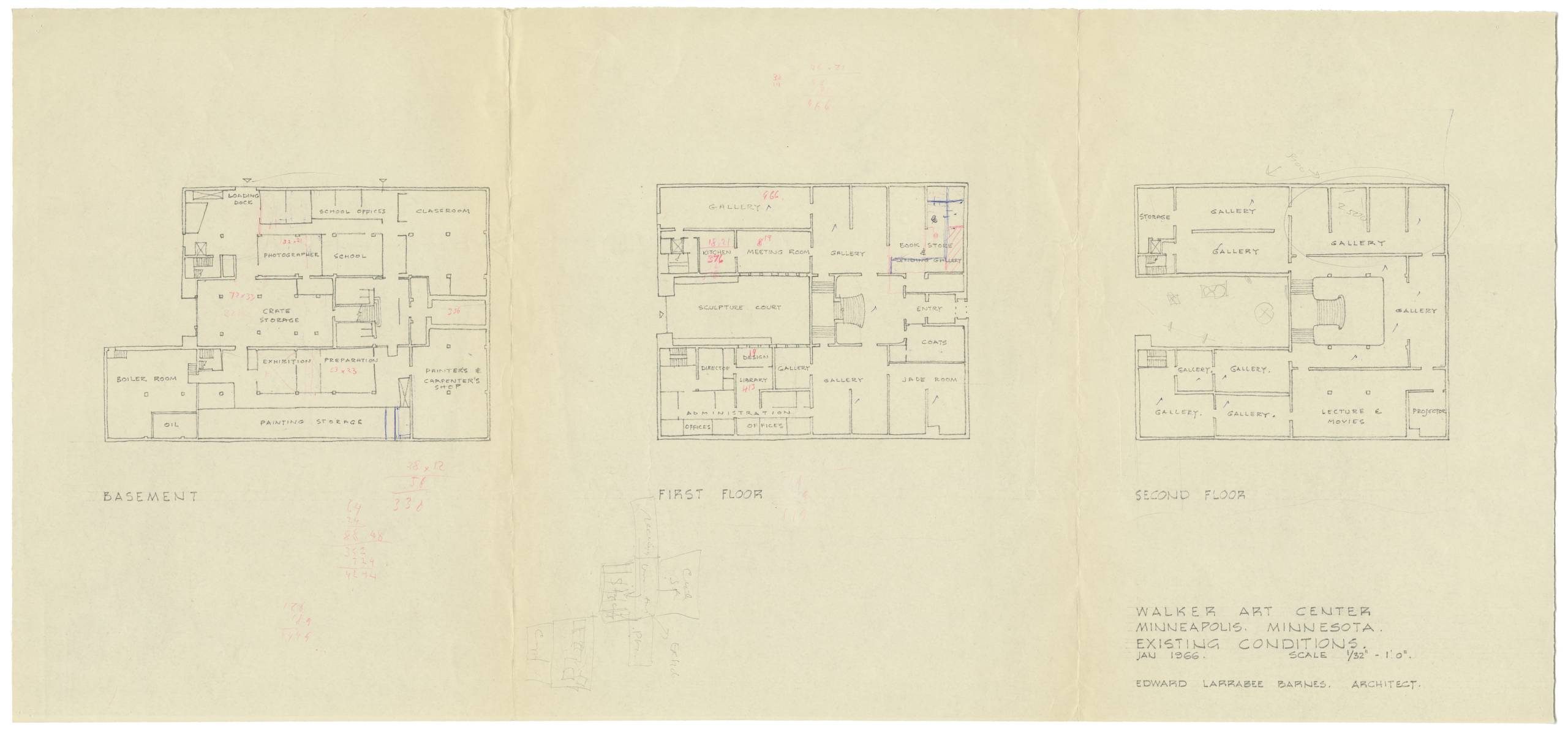

The Walker is a good example of the transformation of a sculpture court over time. Built in 1927 by architects Long and Thorshov, the original Walker Art Center building, known as the Walker Art Galleries, was in the classical style, with an exterior court located in the center of the building. As shown here, the original drawings identify the space as a court, but not specifically a sculpture court, because the Walker did not focus on collecting sculpture until the 1950s. Only in the mid 1960s did it come to be described as a “sculpture court.”

Under the leadership of director H. Harvard Arnason (1951–1960), the Walker began to collect sculptures from living artists, including David Smith, Jacques Lipchitz, and Elie Nadelman. The Walker has continued to acquire contemporary sculpture and now has a collection of hundreds of works. Writing in the first sculpture book of the collection in 1968, Walker Director Martin Friedman commented, “Even as this catalogue is being prepared, important works are being acquired by the museum and consequently this publication becomes essentially a report on the status of the collection as of December 1968.” (Twentieth Century Sculpture in the Collection of Walker Art Center, 1969, pg. 5)

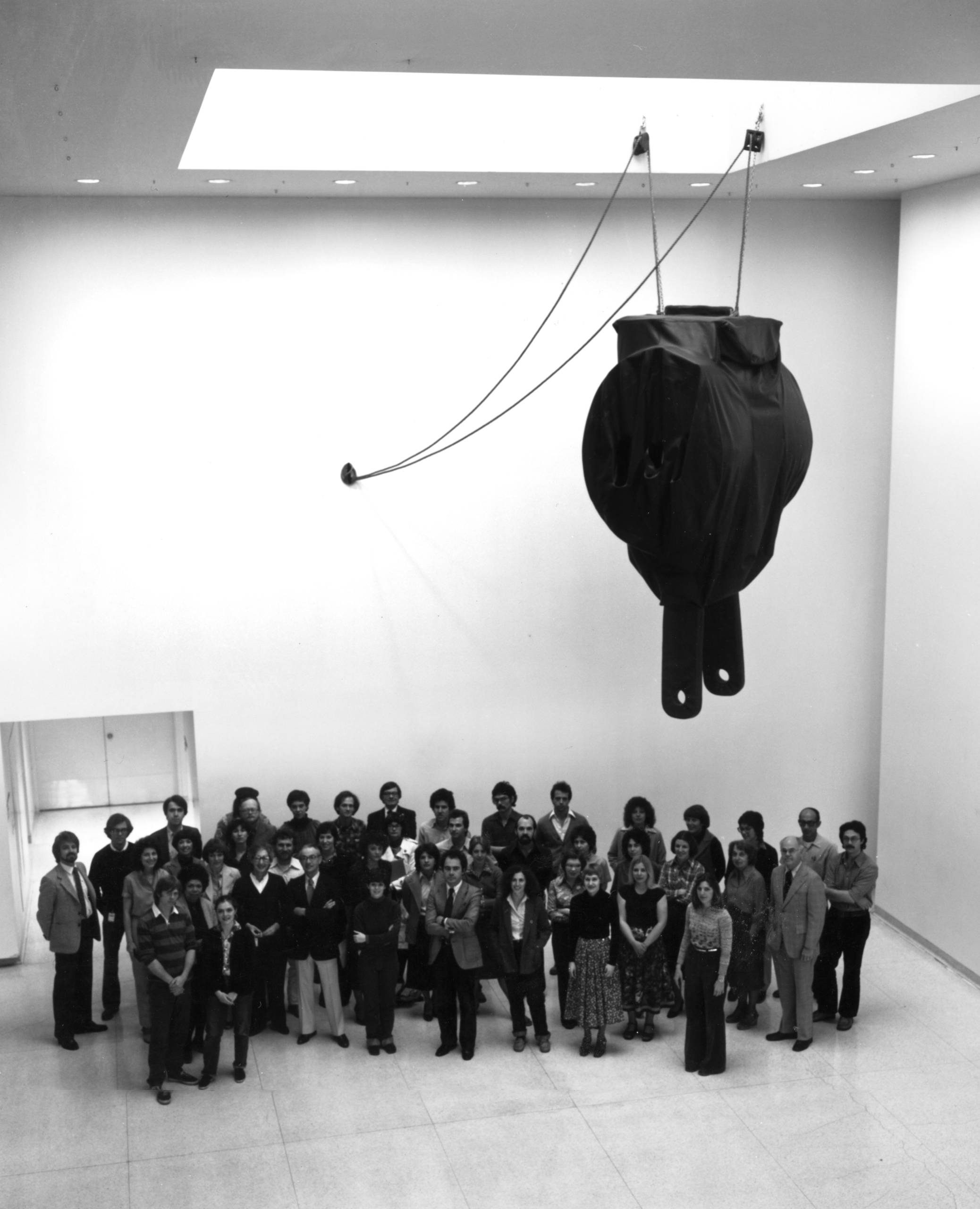

The sculpture court was a small exterior space connecting galleries, meeting rooms, and administration offices. As in earlier examples of courts, the sculpture needed to be small enough to fit in the space and made from materials that could withstand the elements. That meant that many sculptures could only be displayed in interior spaces, such as Claes Oldenburg’s Three-Way Plug (1975), installed in the lobby of the Edward Larrabee Barnes building.

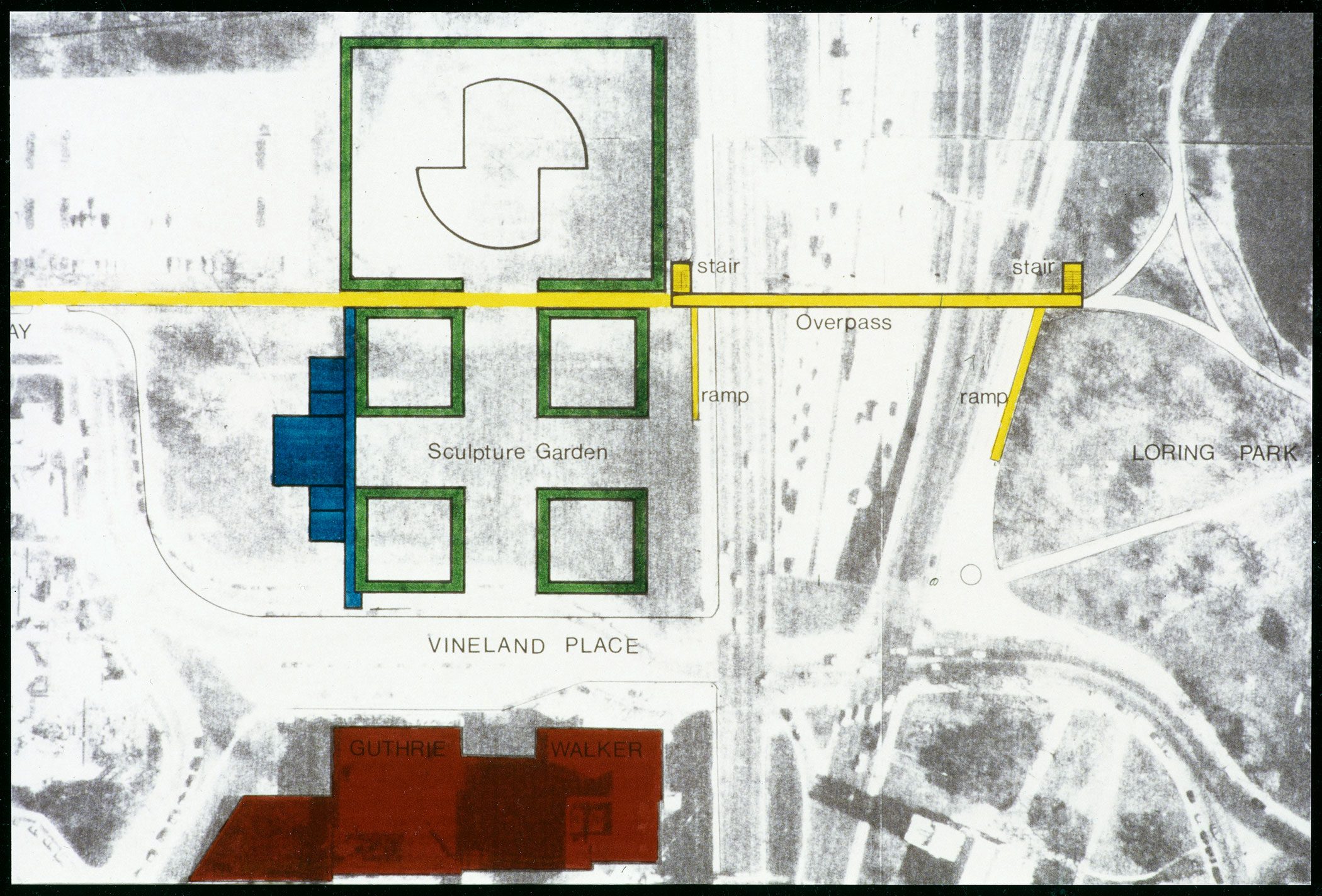

While no sculpture court existed in the 1971 Barnes building, the architect and the Walker’s director began working on a sculpture garden once the museum opened. It would not become a reality until almost 20 years later, when the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden debuted. The original garden used a classical style: a courtyard with four courts and a fountain.

Opened in 1988, the outdoor Minneapolis Sculpture Garden remains a beautiful and popular space for sculpture; it also exhibits works of a certain size and material, just like in the original Walker Art Galleries’s exterior court. The conversion of Gallery D/Perlman for Sculpture Court counts as the first time the Walker has had an interior court.

When the Walker expanded in 2005, architects Herzog and de Meuron created new gallery spaces and the McGuire Theater. As part of that expansion, the former administration wing, behind Gallery 3, became Perlman Gallery. Because of its size and accessibility to collection storage, it was the perfect space in which to display very large sculptures, such as Charles Ray’s Unpainted Sculpture (1997). While Perlman Gallery is not technically called a court, one could argue that it functions like one. It is a contained interior space with a high ceiling and acts as a connecting space between Gallery 3 in the Barnes building and the Friedman Gallery in the Herzog and de Meuron building.

The exhibition currently on display contains smaller sculptures that can only be displayed in a controlled environment, where the temperature and humidity are stable and there is no excessive light or weather. While some of the works may be familiar to visitors, like Alexander Archipenko’s Turning Torso (1921/1959), many others on view have never been seen before in the galleries. These include Between Friends (1984) by artist Arlene Burke-Morgan, an artist who worked in Minnesota for many years. The ceramic sculpture depicts faces that seem to be singing and emerging from what looks like a tree trunk. Created in 1984, the Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Purchase Award winner has not been exhibited until now.

While the works on view are diverse in their use of materials and composition, they all are interpretations of the human figure. In works like Ernest Trova’s Study: Falling Man (Wheel Man) (1965), it’s easy to recognize the human figure; others, like Sherrie Levine’s Black Newborn (1994), may not be. Inspired by Constantin Brancusi’s Newborn (1915) series, Brancusi abstracted a child’s sleeping head in marble, showing only a hint of a nose or eyebrow. Taking the concept further, Levine created a work in glass that is an abstracted oval resembling an egg.

In the spirit of the Renaissance, visitors are encouraged to sit and draw the works. The gallery includes folding seats, paper, and pencils for the practice of drawing the human figure as created by contemporary artists. The quiet of the gallery provides a respite to sit and study the sculpture. One can return multiple times to observe and learn something new, either from study or active drawing.▪︎

Experience Sculpture Court for yourself at the Walker Art Center through August 30, 2026. Learn more and get tickets here.